Two things that spring to mind on October 20th; my mum’s birthday and the Mau Mau uprising.

October 20th is not the exact day of my mother’s birth, but she chose for herself this date because of its significance in Kenya’s fight for independence against the British Imperials.

To understand why my mother chose October 20th, also known as Mashujaa Day (Heros Day), I will have to take you on a trip down memory lane.

My mother, Irene Njeri, was born circa 1956, at a time when Kenya was on the verge of a bloody war with the British colonial government. Even though not a Mau Mau fighter himself, her father did what many men in that time were doing, and he supported the Mau Mau.

The genesis of the Mau Mau rebellion was a long-standing dispute for land, to which the Mau Mau believed African land belonged to African people. The Mau Mau insurgency against the British colonial government sought independence and the return of traditional homelands.

Mau Mau means Mzungu Aende Ulaya, Mwafrica Apate Uhuru – the white man should go back to his country, and leave the African to regain his independence

By the late 1920s, most prime highlands were home to white settlers who, in turn, turned the land into commercial coffee, tea and pyrethrum plantations. Of course, like other grassroots supporters, my grandfather, in his role, made sure that he had a constant supply of food for Mau Mau fighters.

Overseeing the unfolding MauMau resistance in Kenya, the British colonial government, led by then Kenya’s Governor, Sir Philip Mitchell, downplayed the significance of the MauMau uprising as a thorn in the flesh. Admitting the power and potential to overthrow the colonial forces in Kenya would have been tantamount to admitting failure.

How could an esteemed Governor admit, then, that he was losing to savages, as they called the Mau Mau? Not to mention, the growing resentment of white racial supremacy in Kenya had long manifested through land grabbing by white settlers, the introduction of Christianity and a Eurocentric education system, not to mention public lynching and execution by hanging.

An Imperial Decline

Back in Britain, the British Empire was already dealing with its mess; the embarrassing abdication of King Edward VIII to marry American divorcee Wallis Simpson, the accession of a reluctant King George IV, and growing decolonisation concerns in the Empire’s colonies.

King George VI sent his daughter, Princess Elizabeth and her husband, Prince Phillip, on a Royal tour of the Commonwealth countries with Kenya as their first stopover. The King, who was too ill to make the trip himself, sent his daughter on the ‘diplomatic mission’ when the British propaganda machinery was working hard to boost the spirits of the British people.

On February 6th 1952, 6 days after Princess Elizabeth’s arrival in Kenya, her father, the King, succumbed to coronary thrombosis. Princess Elizabeth, who was boarding at Sagana Lodge, right in the heartland of the Kikuyuland, flew back to Britain from Kenya as Queen Elizabeth II, making her the first Sovereign in over 200 years to accede while abroad.

1952 was beginning to look like a bad year for the British Empire: From King George’s death in February, the Queen’s delayed coronation and the Queen Mother’s death, not to mention Winston Churchill’s grip on power despite his failing health.

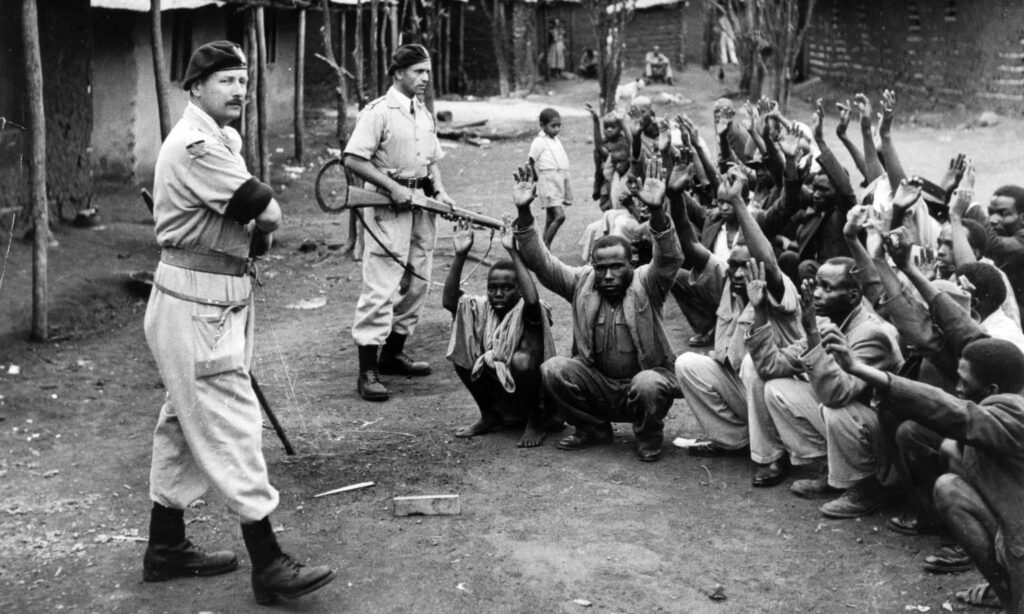

Part of the propaganda used by the British colonial government juxtaposed white saviorism and its purported heroism against a backdrop of black savagery. Like most wars, the first casualty is always the truth.

The spin-doctoring of the ongoing resistance in Kenya by the Mau Mau took place with the glorious intention of dehumanising the fighters as savages out to brutalise innocent European settlers: this narrative was common among colonial depictions of Africa as the dark continent.

Death of controversial Senior Chief Waruhiu

By the time of my mother’s birth, Kenya was already under a National State of Emergency order, decreed by Governor Sir Evelyn Baring, who on arrival in Kenya met homegrown hysteria by white settlers who wanted action taken against the Kikuyu fighters.

The unfolding propaganda and resistance had reached a crescendo. Destruction of settler property was more daring than ever; the Mau Mau assassinated t Kikuyus loyal to white settlers. Sir Evelyn Baring appeared as Messiah, one who could help navigate the Mau Mau menace.

Hot on the heels of the Governor’s arrival was the bold assassination of Senior Chief Waruhiu on October 9th, 1952. The senior chief was a darling of the British colonial administration. Praised for his welcoming take on Christianity and Western values. Chief Waruhiu took to British law, and order like a fish takes to water.

The senior chief embodied this by doing his part to look like a black Englishman; He believed and breathed white superiority. To the Mau Mau, Senior Chief Waruhiu was a pro-European traitor, a pariah and dangerous precedence, and he, as a result, deserved to die.

His assassination was received with jubilation in Kikuyuland as poetic justice. Yet, for Sir Evelyn Baring, the senior chief’s murder was the tipping point. The British government mourned Senior Chief Waruhiu as a fallen servant of the British Crown.

State of emergency

October 20th, the day my mother rebirthed herself, is forever etched in the memories of Kenyans. On the evening of October 20th, 1952, Governor Baring declared the State of Emergency.

The code-name assault oversaw, on the early morning of October 21st, 1952, the arrest of Mau Mau protagonists Paul Ngei, Fed Kubai and Bildad Kaggia, and Jomo Kenyatta.

Like many Pan-Africanists of his time, Jomo Kenyatta lived in the UK for close to 15 years, even marrying an English woman, Edna Grace Clarke, in May 1942. He also studied at the London School of Economics.

But when Jomo relocated back to Kenya to join the nationalist movement, he was more anti-colonial than ever. He was a sore contrast to the black Englishman, Senior Chief Waruhiu.

To deter other anti-colonialists and mitigate settler anarchy, the colonial government took a risky decision by prosecuting Kenyatta along with five of his deputies: Bildad Kaggia, Paul Ngei, Achieng’ Oneko, Fred Kubai, and Kungu Karumba.

The Kapenguria six stood accused of fomenting a revolution and sent to Kapenguria, one of Kenya’s brutal outposts, for a maximum imprisonment of seven years with hard labour: Doomed to die in desolation.

For all its Empire’s grandiosity and political grandstanding, the sentencing of Kapenguria 6 peers did little to lighten the brutality of Mau Mau fighters.

These fighters were known to mutilate men, women, young or old, who were suspected to be loyalists. The most notable incident is the Lari Massacre. Ninety-seven Lari residents burnt to death in their huts, and those who tried to escape were hacked to death.

These attacks came after the Mau Mau took offence at the loyalist Home Guards and their families, including Chief Luka-a a loyalist and beneficiary of the colonial government land allocation, all who lived in Lari.

In response, the colonial government took this attack as a cue to amplify its propaganda machinery. Thus further detailing in gruesome detail the savagery of the Mau Mau.

But in a calculated manner, failing to mention the massacre prompted retaliatory attacks by security forces — British, American, local police and King African Rifles — during which 400 Mau Mau were killed.

The Mau Mau struggle

Forced eviction, like that of my grandparents, marked the colonial government’s first major assault on a civilian population, or what was referred to as Mau Mau sympathisers.

Similar to the deportation of South Africans to homelands by the apartheid government, Kikuyus too were deported to Kikuyu reserves or ‘mixed villages’, which were manned by armed home guards.

My mother was only an infant when the raids happened, “From what I have heard, the door to our house was kicked in by some white soldiers and local home guards. Someone had reported my father and mother as Mau Mau collaborators.” she narrates.

“The soldiers pulled my parents to one side and my three sisters and me to another corner. There was barely enough time to pack our belongings, and we had no prior warning. My parents were packed into our lorry and carried off into the night. I later learnt my father was in Manyani, a brutal prison captured forest fighters.”

“Manyani, I understood, was covered with barbed wire from the windows to the fences to bar any escape. Armed King African Rifle soldiers stood guard at the watchtowers, ready to shoot any escapees. Many people were gunned down while trying to escape. ” She also recounts that her mother was sent to Kamiti women’s prison and sentenced to death by hanging for her role in collaborating with the Mau Mau fighters.

I have heard my mother tell this story countless times, with the same pain in her voice. For even though she was an infant, the indiscriminate and inhumane removal changed her family’s destiny.

My mother was to find herself in the care of her 8-year-old sister, the four girls, separated from their parents arrived in an overcrowded reserve, or what the Jews in the Holocaust called a Ghetto.

My grandparent’s house got razed to the ground, together with all documentation that could indicate the date or year of my mother’s birth. Although my grandmother was spared from execution, the violence, torture and trauma of detention took a toll on my grandparents’ marriage.

John Nottingham

Colonial Brutality and generational trauma

My grandmother died of breast cancer when my mother was around ten years old. On being released from the unbearably hot and remote Manyani, my grandfather remarried and decided he no longer wanted to be a father of girls.

The trauma of the removal and detention tore at the very fabric of my mother’s family. This generational trauma continues to wreak havoc in my family up to date.

By 1963, it became inevitable for Britain to grant Kenya its independence. Yet, back in Britain, the would be no public acknowledgement of gulags, detentions, removal and crimes against humanity for the hundreds of thousands of Kenyan men, women, and children.

The impact of trauma from the detention camps and prisons followed many men and women into their graves. For many survivors, it was too painful to talk about the beatings, rape, castration or witness to murders.

Many men, and women, unable to cope with the physical, psychological or economic scars, passed on the brutality to their children, and thus a cycle of generational trauma was born.

To date, the topic of the Mau Mau is rarely spoken about; it is not taught in schools, and there are no monuments for Mau Mau in Kenya. My Boss and former colonial District Officer, John Nottingham, did his part in making sure the atrocities of the British Empire were made known. John was on the leading march towards agitating for the preparation of victims of colonial brutality.

For many years, October 20th was referred to as Kenyatta Day, a public holiday that in a way only chose to focus on Kenyatta as a protagonist, ignoring the thousands of men and women who died so that Kenya could be a sovereign country.

However, with the promulgation of a new constitution in 2010, Kenyatta Day was renamed Mashujaa Day (Heros Day), a progressive move towards honouring those who fought and died in the struggle for Kenya’s independence.

Today I celebrate my mother, for each hard day that she got through brought me to this place where I can share her stories.